The chronicle of self-learning - mov, Turing Machines and Compilers

by Luca Di Sera

“And so for a time it looked as if all the adventures were coming to an end, but that was not to be”

Another adventure is coming to its end as I’m finally reaching the last few chapters of the Crafting Interpreters book, from Bob Nystrom. I already liked the author’s previous book{ Which I have never completed tough }, but I found that this one was by far more interesting { Probably because languages and compilers are by far more compelling to me }. While the first part was interesting but a bit boring at some points { It may be because some things I already knew }, the second half of the book is beautifully crafted, furthermore it is a pleasure writing in pure C after all these years { especially now that I’m full on the C++ library and am reading wall of text on its abstractions almost every day }. It has an everlasting elegance and minimality that I didn’t know I was missing.

Furthermore, I must praise the book as it is a kind of book I searched for a lot. I will someday find the strength and time to read the dragon book, but for starters, a more practical, scoped, introduction to compilers was something that I always needed. I’ve tried many books at that, but either they skip some important information for a complete beginner ( like using generated scanners and parsers ) or they lack any kind of real detail. Crafting Interpreters has hit that sweet spot for me that I searched for so long.

On the topic at hand, as I do with most books I complete, I have to devise some kind of exciting exercise for reinforcement learning. As always, it should help me revise the topics of the books on a more personal note, it should be practical and it should contain some chance to deepen some topics. While sometimes it can be difficult to find the concept of such an exercise, it is straightforward that it should be some kind of compiler { a bytecode + simple virtual machine one as in the second half of the book at that }. But the problem is: Which language should I implement?

BTW, for those who recognized the title reference, I have a small story. When I was little, and Narnia was one of the new cool things, with the upcoming movie, I decided to buy the big thousand-and-spare pages book with all the chronicles in it. Little me was so happy, less so when the same day { as it was my birthday } I received my second and third copies as birthday’s gifts { ugh }. Well, in the end, this was one of the most boring, annoying, poorly-written books I have read. So much that, about 200 pages in, I felt like puking at the sole idea of opening the book again. I’m not sure where my three copies { Oh the Irony of having 3 copies of one of my most hated books and zero copies of some of my most loved ones } are, but I hope that they’re burning in hell. Anyway, the idea of referencing that book came to me as I vividly felt a kind of uneasiness that brought me back to that time as I was laying out the details of this upcoming exercise.

MOVing along

We don’t need another useless, badly designed, horribly implemented toy language. This was the first thing I felt when I started designing this exercise. There are many existing languages that are perfect for a first compiler.

I was epsecially leaning on, maybe, Scheme, a Z-machine or the obvious PL\0. While this was the sanest choice, I had the worst of luck by accidentally { \s } remembering a beatiful paper that I have randomly read some weeks ago.

Stupid me, then, decided that “We don’t need another useless, badly designed, horribly implemented toy language” - but no one will be hurt if some average joe goes at it! And so comes Tummys

They’re comin’ outta the goddamn walls!

So, what the hell is a Tummys? Well, Tummys is my will-be { or so I hope } toy language that acts as a DSL for deterministic Turing Machines. There are some design seeds that I chose for Tummys:

- { Almost } everything is a TM.

- The basic programming paradigm is based on TMs’composition, akin to functional composition.

While bare, they were enough to start designing the language.

How are our TMs defined

For Tummys we are mostly using the classic intuition of a TM with a configuration, a read-write head and a tape. A TM reads a symbol from the current tape’s cell under the read-write head at each step and writes a symbol on that cell, moves either left or right and sets to a new state. These actions are chosen in accordance with the TM’s configuration. A TM stops its execution when it reaches a halt state in its configuration. Our tapes are one-dimensional and infinite in both directions. Each cell of the tape has either a character from the input alphabet or the blank character written on it at each step.

Mathematically, we think of our TMs using a seven-tuple model I’ve seen in The Computability, Complexity & Algorithms course on Udacity. Taking from Lesson 2: Turing Machine resource pdf of the course :

Mathematically, a Turing machine consists of:

- A finite set of states. (Everything used to specify a Turing machine is finite. That is important.)

- An input alphabet of allowed input symbols.

- A tape alphabet of symbols that the read/write head can use

- It also includes a transition function from a (state, tape symbol) to a (state, tape symbol, direction) triple. This, of course, tells the machine what to do. For every, possible current state and symbol that could be read, we have the appropriate response: the new state to move to, the symbol to write to the tape (make this same as the read symbol to leave it alone), and the direction to move the head relative to the tape. Note that we can always move the head to the right, but if the head is currently over the first position on the tape, then we can’t actually move left. When the transition function says that the machine should be left, we have it stay in the Q same position by convention.

- We also have a start state. The machine always starts in the first position on the tape and in this state.

- Finally, we have an accept state,

- and a reject state. When these are reached the machine halts its execution and displays the final state.

Tummys uses bi-directional infinite tapes so we don’t have the constraint that we can’t move left at the start of the input. This is the first time that I’ve seen a separate input and tape alphabet, but we use this same convention in Tummys. Furthermore, the input alphabet cannot contain the blank symbol that instead must be contained in the tape alphabet. This is useful as this means that we can’t accept input strings that have blank symbols.

The TM in Tummys works like any classic TM you can think about given these constraints.

A, b, c, d, e …

This section was pretty mangled. In the beginning, this post was about a dozen times larger. I iteratively simplified Tummys as I was adding far too much-unneeded complexity. This is one of the things I cut from the most. At the start Tummy had a kind of type system based on alphabets. Furthermore, I was designing some things around another entity that modelled languages. In the end, most of this was scrapped off, so that alphabets are pretty bare. I decided to still keep a minimal iteration of them to use in the definition of TMs as I think they can provide a useful way for the compiler to spot some logical errors.

One of the basic building blocks of Tummys is alphabets. Alphabets are a collection of unique comma-separated characters ( between a pair of single quotes ) between a pair of braces, as follows:

['0', '1']

This is, for example, the binary alphabet. Alphabet with repeating characters are collapsed to the set of their unique elements:

['0', '1', '1']

This is the same alphabet as above.

Given two alphabets and Tummys provides the following operation on them:

- trough the binary operator ‘&’

- trough the binary operator ‘+’

- trough the binary operator ‘-‘

Alphabets can be assigned to an identifier as follows:

#BINARY ['0', '1']

The identifier must be a sequence of characters that are elements of [A-Z]. After an alphabet is assigned to an identifier, the identifier acts as an alias for the alphabet and the two can be replaced by one another without changing the meaning of the program. Assigning to the same identifier more than once is an error.

Creating and executing TMs

First of all, we have to have TMs to work with for Tummys to make sense. While Tummys will provide some default TMs, it gives us the chance to define our own. This is how a TMs definition looks like in Tummys:

:: odd ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> (S, '1', R),

S [' '] -> (1, ' ', L),

1 ['0'] -> (REJ, '0', R),

1 ['1'] -> (ACC, '1', L)

}

This is a Turing Machine on the alphabet [‘0’, ‘1’] ( Binary ) that accepts if the input string represents an odd number. Breaking this down we have:

- The “::” define operator that opens the definition for a TM.

- The identifier that will be used to reference the TM { odd in this case }. An identifier starts with a lowercase letter and is composed of any number of characters.

- The input alphabet that the TM will accept, in this case [‘0’, ‘1’].

- The tape alphabet, defined as the union between two alphabets and , where and is the character representing the blank character on the tape {e.g the absence of a character on the tape }. It is an error to have the blank character appear in the input alphabet or to have a tape alphabet that isn’t of the form .

- The transition table defined as a block starting with “{“ and ending with “}” with a series of comma-separated transition declarations in it.

A transition declaration has the form:

state alphabet -> transition

Where:

- “state” is a state identifier of the form [a-zA-z0-9]

- “alphabet” is an alphabet such that where is the tape alphabet of the TM

- The “->” transition operator

- A triplet of values composed as (new-state, write, direction) where “new-state” is the state identifier that refers to the state that the TM will transition to, “write” is a character , where is the tape alphabet of the TM and direction is a symbol , defining the direction that the head should move. move the head to the right while move the head to the left.

The special move direction symbol ‘^’, leaves the head where it currently is. A transition declaration of the form:

N A -> (N1, s, ^)

is equivalent to:

N A -> (N2, s, R)

N2 A1 -> (N1, _, L)

where , and is the tape alphabet of the TM.

This is mostly equivalent to actually having the head be able to stay put in the first place. But there is an edge case where the character to the right of the head is not a valid character in the alphabet, meaning that, as per Tummys’ rules, the machine would halt immediately. If the head was effectively never moved that character may not have been encountered. A way to partially resolve this is to have the head move to the opposite direction of the last made movement and then to the opposite of that. This is so that we can be sure that we will not encounter an unknown character as we pass in a place where the head has already been.

Unfortunately, this too has an edge case where there was no prior movement to a stay-put transition. In that case, a direction must be chosen, at random or in a fixed way. Tummys, for consistency reasons, will always expand to a right-left move.

A special write character _ is used to denote that no character has to be written, leaving the character that was already there. For example the transition declaration:

S [a1, a2, ... , an] -> (S1, _, d)

is equivalent to the following transition declarations:

S[a1] -> (S1, a1, d),

S[a2] -> (S1, a2, d),

...

S[an] -> (S1, an, d)

This is true whenever the _ symbol appears in a transition declaration, independent of where it appears. This means that a delegating transition to a parametrized Turing machine ( which we will see in a bit ) on which the _ is used as a parameter, such as the following:

S [a1, a2, ... , an] -> M<_> -> (...)

is expanded to:

S [a1] -> M<a1> -> (...),

S [a2] -> M<a2> -> (...),

...

S [an] -> M<an> -> (...)

A _ symbol appearing in the “transition” part of any type of transition declaration is always resolved after every other expansion is complete.

, and are special state identifier referring to the starting state, the reject state and the accepting state. At least a transition declaration from state must be present in each TM definition. The and state are implicitly defined and have no transition from them. While some transition declaration may be given for them, the TM will halt as soon as they will be reached making those declarations useless.

At least one transition to the or states must be present in any TM definition.

A state identifier is implicitly defined the first time it is encountered in a transition table for a given TM. If a transition declaration from on the alphabet comes after a transition declaration from on the alphabet and is non-empty, the transition from on wil follow , the transition declaration on .

When a character for which no transition from the current state exists is met, the TM halts on the rejecting state immediately.

The second type of transition declaration is the delegating transition of the form:

state alphabet -> expression -> transition

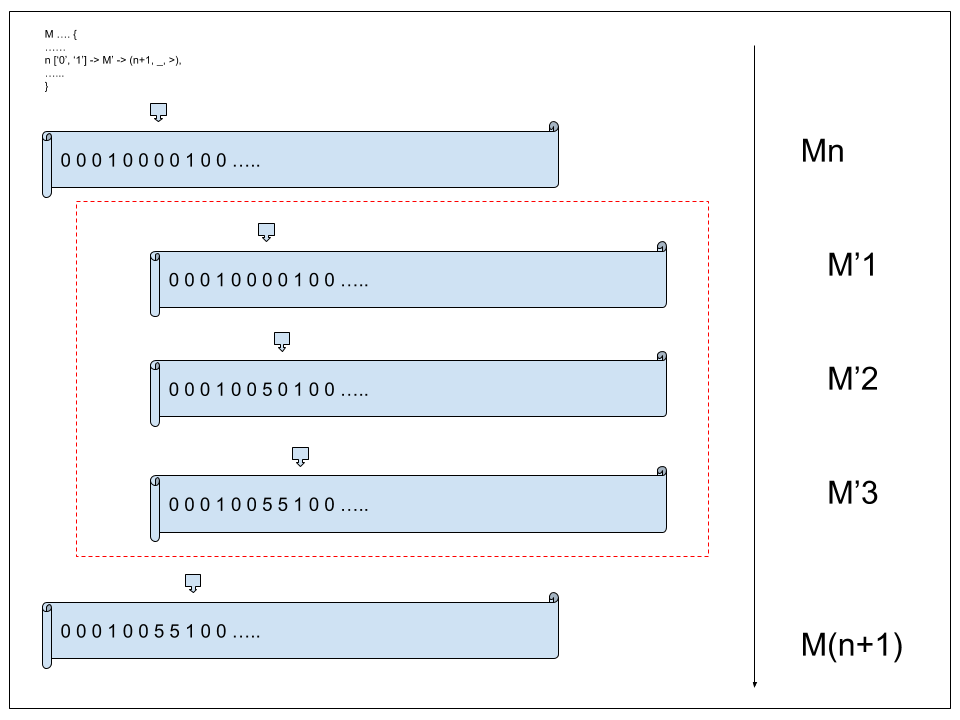

Where “state”, “alphabet” and “transition” are defined as above. “expression” is a valid Tummy expression ( e.g a sequence of TMs ). An image can help us understand this concept.

Basically, we have this TM that is executing on the tape . is currently at state when it encounters a delegating transition. The transition is delegated to , which is a TM that writes two 5s to the tape and then halts. is executed on the original tape with its head starting at the position where the head of was when it encountered the delegating transition. After halts the original TM continues its execution on tape $T$ with its head moved to where left it.

This is a shortcut for the following situation. Let’s say we have the following Tummy’s TM definition:

:: M' A A' {

S A''' -> (1, a, R),

1 A''' -> (2, a, R),

2 A''' -> (ACC, a, R)

}

This is a TM that moves the tape to the right three times and writes three times the character . Now let’s say we are defining the TM , that at some point in its execution has to do the same steps as , instead of rewriting the logic we can delegate to :

:: M A A' {

...

N A'' -> M' -> (N',...),

...

This is equivalent to expanding the transition table of in at the point of the delegating transition as follows:

:: M A A' {

...

N A'' -> (M'S, _, ^),

M'S A''' -> (1, a, R)

M'1 A''' -> (M'2, a, R),

M'2 A''' -> (N'', a, R),

N'' A' -> (N', ...),

...

We basically inline the TM that is the result of expression’.

First, the machine transitions to the initial state of the delegated to TM. We use an intermediary transition that leaves the tape and head unchanged, instead of expanding the original delegating transition directly to the starting state transition declaration of the delegated to machine, to avoid problems with multiple starting state declaration or multiple delegating declarations on different alphabets.

Each transition that would transition to or transitions to $$ N \prime \prime $ instead.

is an intermediate state that for every character will transition to with the transition triple .

Delegating Transitions are a way of reusing TMs by executing them from another TM.

Given a TM with a tape alphabet that has one or more delegating transitions to other TMs with tape alphabets , the tape alphabet of is considered to be where is the blank symbol for .

Lastly, Tummys supports a second type of TMs, parametrized TMs. Parametrized TMs are inspired by C++ templates and C’s macros and are a mean to generate a series of similar TMs that differ in some way. For example, let’s say we are making a program that requires two TMs: , that substitutes the first blank character for the character ‘#’, and , that substitutes the first blank character for the character ‘*’. A way they can be defined is as follows:

:: M A A+['#']+[a] {

S A -> (S, _, R),

S [a]-> (ACC, '#', R)

}

:: M' A A+['*']+[a] {

S B -> (S, _, R),

S [b] -> (ACC, '*', R)

}

As you can see they differ only in what they append to the tape. Instead of replicating the code, we can parametrize a single TM as follows:

:: <c> append A A+[c]+[a] {

S A -> (S, _, R),

S [a]-> (A, c, R)

}

append can then be used in an expression as follows:

append<'#'>

The compiler will generate a new definition replacing all appearances of c with “’#’”. They are more C’s macros than C++ templates apart from the syntax.

Expressions

In Tummys there exist a single expression type, The conjunction of TMs that has the form:

M M1 M2 M3 M4 ... MN

Each expression, no matter where it appears, is firstly compacted and then compiled. The process for which an expression is compacted is through the conjunction of TMs.

Given any two turing machines and , for which and are disjoint, their conjuction is the turing machine , where is the set of additional states that are needed for the conjuction and is a transition function with signature that describes the new transition table derived from the original TMs.

Each transition to the rejecting or accepting state in is substituted to a transition to a state that start the process of rewinding the tape.

When we go from a state to a state , a series of additional steps are added to move the tape head to the leftmost cell that is not blank so that the execution of the states of the second TM starts from the perceived start of the tape. This means that the conjunction of a Turing machine that moves elements to the right without modifying the tape, writes a blank symbol, and then moves one element to the right, effectively moves the perceived start of the tape cells to the right.

An expression of the form:

M M1 M2 M3 M4 ... MN

is equivalent to

In a more practical way, we apply the following algorithm.

Let’s suppose that we have the following two TMs:

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC, '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC, '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, '1', R)

}

The expression:

M' M

is compacted to a new Turing machine by the following process.

First, we change the name of their states so that the two set of states are disjoint ( this is true for implicitly declared states and transitions like the REJ state too).

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

then start defining with the transition table of :

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

:: M'' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

Then we expand so that each transition to or will transition to a new state that starts the rewind process and we add the necessary transition declarations to rewind the tape:

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

:: M'' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [1] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

REWIND [0, 1, ' '] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [0, 1] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [' '] -> (ACC, _, R)

}

The rewind TM first moves once to the opposite direction of the last movement ( or stays put if the last movement was ‘^’ or its equivalent expansion), then moves to the left until a blank character is encountered. On the first blank character, the tape gets moved to the right to the last encountered non-blank characters and the rewind machine halts.

We then expands ‘s alphabet with the alphabet from :

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

:: M'' [0, 1]+[0, 1] [0, 1]+[' ']+[0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [1] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (REWIND, '0', R)

REWIND [0, 1, ' '] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [0, 1] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [' '] -> (ACC, _, R)

}

We add the states and transition declarations of to and connect the accepting state of the rewind machine to the starting state of :

:: M [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [1] -> (ACC, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (ACC, '0', R)

}

:: M' [0, 1] [0, 1]+[' '] {

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

:: M'' [0, 1]+[0, 1] [0, 1]+[' ']+[0, 1]+[' '] {

S [0] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [1] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

S [' '] -> (REWIND, '0', R),

REWIND [0, 1, ' '] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [0, 1] -> (REWIND2, _, L),

REWIND2 [' '] -> (S', _, R),

S' [0] -> (1, '0', R),

S' [1] -> (1, '1', R),

S' [' '] -> (1, ' ', R),

1 [0] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [1] -> (ACC', '1', R),

1 [' '] -> (ACC', '1', R)

}

And with this, we are done. is the new accepting state. In this particular case, we have the TM that, on any valid input, writes ‘0’ in the first cell, and ‘1’ in the second cell then halts.

The unary expression of the form:

M

is compacted to itself.

A compacted expression is evaluated to the final tape state resulting from the application of the empty input on the resulting TM. This is a remnant of a previous iteration of Tummys and is now unnecessary.

Special Turing Machines

Tummys provide a series of inbuilt Turing Machines that enables special capabilities or streamlines some process.

String Literals

In Tummys, a string literal is a collection of characters between two double quotes:

"Tummys"

"Hello World"

"Here I am"

String literals are themselves Turing Machines. In fact, given any string literal , we build a corresponding TM that writes something to its tape and halts independent of its input tape, as long as it is valid.

Any string literal of the form “ “ is equivalent to a turing machine of the form:

:: M A A+[a] {

S A+[a] -> (1, c1, R),

1 A+[a] -> (2, c2, R),

2 A+[a] -> (3, c3, R),

3 A+[a] -> (4, c4, R),

....

N A+[a] -> (ACC, cn, R)

}

it follows that the unary expression:

M

is equivalent to the expression of the form:

S'

where is the Turing machine that writes to its tape and is a string literal of the form “ “.

String literals are the idiomatic way of building input tapes. An expression of the form:

M1 ... MN S'

where are Turing Machines and is a string literal of the form “ “, is equivalent to running the compacted Turing machine:

M'

that is compacted from the expression on the input tape which has written on its cells, starting at some cell , with the head of initially pointing at .

The second idiomatic use of a string literal is to streamline input-state independent write operation on some tape through the use of a delegating transition:

...

N A+[a] -> "Hello World" -> (N', _, <)

...

is the same as adding a series of states that writes “Hello World” on the TMs tape starting at the cell that is currently pointed to by the head, ending on the cell containing the last written character, “d” in this case, and transitioning to state .

Side Effect TMs

I/O TMs

A sequence of special Turing machine is provided for input/output purposes.

The TM is a special Turing machine that reads a line of input from the user and writes it to its tape halting afterwards.

The TM is a special Turing machine that reads a single character of input from the user and writes it to its tape halting afterwards.

The TM is a special Turing machine that writes all the contents of its tape, starting at the leftmost non-blank character, to the output and then halts, leaving its tape and read-write head unchanged.

State machine

The state machine is a special Turing machine that, when composed with another machine, writes ‘A’ to its tape if the machine it was composed with, when run, ends on the accepting state and ‘R’ otherwise. As with everything in Tummys, non-halting Turing machines are considered undefined behaviour.

Debugging and Inspecting machines

This is a category of machines that I’m still unsure about. They would provide a way to attach a debugger to a TM so that information about its execution can be shown to the user.

For example, the machine would run a given TM until the starting state is met, outputting information about the tape, state and followed transition at each step to the user.

Inspecting machines would be similar but would give information about a machine configuration, alphabet or particular transition. For example, would print to the user the expanded transition table of a given machine.

I’m unsure about it as it may be better to provide such functionalities through the Tummys environment ( eg. its compiler or interpreter or other tools ) than directly as language constructs.

Some examples

Here there are some examples of valid Tummys programs. I prepared a Github gist with some snippets of code that can be run on turing-machine.io to graphically see the TMs in action. For practical reasons, not every state is expanded completely ( for example a state that in Tummys would be expanded to states over the whole alphabet may be simplified on the blank character that is the character we are expecting to be there ).

Is divisible by 10?

#DIGITS ['0', '1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8', '9']

:: <A, A', a> toEnd A A'+[a] {

S A' -> (S, _, R),

S [a] -> (ACC, _, ^),

}

:: divisibleBy10 DIGITS DIGITS+[' '] {

S DIGITS+[' '] -> toEnd<DIGITS, DIGITS, ' '> -> (1, _ ,L),

1 [0] -> (ACC, _, R),

1 DIGITS-[0] -> (REJ, _, R)

}

O S divisibleBy10 I

This is a valid Tummys program that takes as input a line from the user and writes A back if the input represents a number such that is divisible by 10, or R otherwise. We first define the #DIGITS alphabet that contains the digits character from which a positive natural number can be formed. While alphabet and languages were mostly removed from Tummys now, it is still important to use basic alphabets so that we naturally reject an incorrect input. In fact, one of the rules of Tummys is that any unrecognized character that is met automatically halts the TM execution on the rejecting state.

This example would have been interesting for some language related mechanics like decision and recognition, but all of those things were removed from Tummys for complexity reasons.

toEnd is a convenience TM, that is designed to be delegated to, that moves a TM head to the right until the first blank character is met, on which it stops.

We then have divisibleBy10 which is the main TM of this program. It works on the DIGITS alphabet and accepts any input on the DIGITS alphabet that is divisible by ten. This is done by going to the end of the input and then checking if it is a ‘0’. If the input has unknown characters the machine will reject as soon as that is encountered.

This is all wrapped in the OSI idiom ( ) that is Tummys way of checking if a given composition of Turing machines accepts or reject a given input.

Right shift

:: <A, A', a> toEnd A A'+[a] {

S A' -> (S, _, R),

S [a] -> (ACC, _, ^),

}

:: <A, A', a, c> write A A'+[a] {

S A'+[a] -> (ACC, c, ^)

}

:: <A, A', a> moveRight A A'+[a] {

S A'+[a] -> (ACC, _, R)

}

:: <A, A', a, e1, e2> compose A A'+[a] {

S A'+[a] -> e1 -> (1, _, ^),

1 A'+[a] -> e2 -> (ACC, _, ^)

}

:: <A, A', a, e, c> hold A A'+[a] {

S A'+[a] -> e -> (ACC, c, ^)

}

:: <A, A', a> rightShift A A'+[a] {

S A' -> toEnd<A, A', a> -> (1, _, L),

1 A' -> hold<A, A', a, compose<A, A', a, write<A, A', a, a>, moveRight<A, A', a>>, _> -> (1, _, L),

1 [a] -> (ACC, _, ^),

2 [a] -> (1, a, L)

}

This is a bit more abstract and difficult to untangle. Here we see the general programming paradigm of parametrized TMs and the functional aspect of composition in Tummys. You can look at an example of a right shift machine on the binary alphabet in the Github gist. I suggest you do so to better understand the idioms we are using here.

Let’s look at this in small bits. First, we have toEnd, we already know her ( I’m not sure why but I think of Turing machines as females ) from the previous exercise.

We then have two small, simple, TMs : write and moveRight. They both encapsulate a core behaviour of a TM. In fact, they do a single operation that is part of a normal transition, writing a character to the current cell and moving the head ( to the right in this case ).

Now, why would we have to define TMs that do a core operation that can be expressed more easily as a transition?

This is more understandable by looking at the most important difference between a transition of the form (N, a, d) and a transition bit composed by moveRight and write, that is : a transition of the form (N, a, d) is not an expression.

Tummys composition is primarily built on delegating transitions, and as such expanding the functionality of a TM by the reuse of an expression, and parametrized TMs that can build a plethora of similar machine from a logical template.

The fact that a composition of bits of a transition can be built by TMs means that we can delegate to them, effectively adding a transition through a parametrized TM.

Before we look at a pattern that uses this concept, we add the simple TM compose. compose encapsulate the generic idea of building two sequential instruction paths to form a bigger computation.

This is similar to a normal double delegation but done with a single TM that can be plugged everywhere an expression can. The difference between a composed expression and a normal compacted expression of two TMs, that would execute the same logic as the two expressions in the composed one, is that by, sequentially, delegating we don’t rewind the tape.

Now, let’s look at hold. This is the main part of the machine we are trying to build.

To shift right on a Turing machine, we move to the end of the input, move left to the last character, blank it and move right, write the character that we just blanked and move left, move left to the next character, repeat until a blank is encountered.

But how do we know which character we blanked? Turing Machines don’t have any memory of this kind of things.

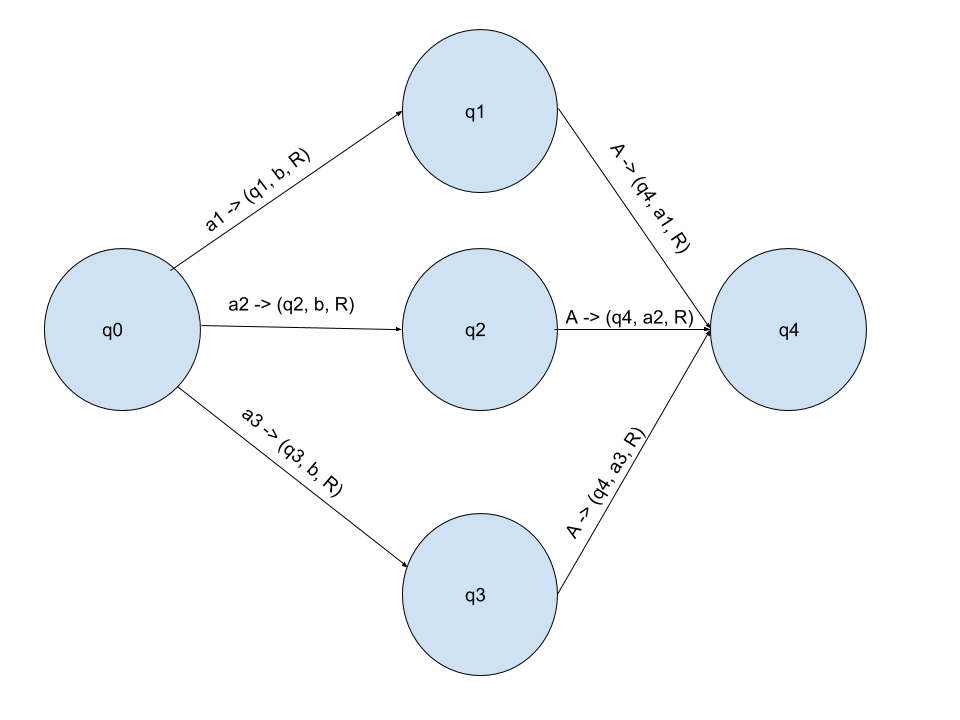

This is done like in the image. We create a path, doing the same thing, for each character but moving to different states so that we can write, in the end, the character which started the path by specifying it directly.

This is what hold does.

hold is the generalization of a pattern where we want to execute an instruction path from a state and then write the character that was met before transitioning from that initial state.

Essentially “remembering” that character or “holding” it in a buffer.

While this is not necessarily useful for a small machine with a small alphabet, like the rightShift on the binary alphabet would be, hold gives us the possibility of scaling the pattern horizontally: in the length of the instruction path to follow. This is thanks to the fact that we can delegate to any expression, be it a single big Turing machine or a compacted Turing Machine made of a sequence of small TMs.

United with another tool that Tummys offer, the _ symbol, we can scale vertically over an alphabet of any size, be it the whole tape alphabet or a subset of it, by writing a single instruction.

Furthermore, this enables us to think of our TMs at a higher level of abstraction and in smaller pieces.

Those last few points completely encapsulate what Tummys compositional tools are designed for. They provide the same structural advantage of functions in other languages, be it maintanaibility or scalability.

Now, what we said before, about the important difference between transition being expressable as expression and being described in a declaration, should make more sense. For the algorithm we are using to shift the input, the diverging instruction path we have to follow is exactly a transition, write a blank and then move right.

This should make sense by now, in case it wasn’t already understandable before, but, to further increment the teaching value of this example, we will look at the expansion that happens in the rightShift TM. We’ll see a concrete case with the following expression:

rightShift<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>

First we concretize rightShift with the given parameters:

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0', '1'] -> hold<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>>, _> -> (1, _, L),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, _, ^)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

We won’t expand the toEnd delegation as that is easily understood.

As we know, in a delegating transition, the first thing that gets expanded is the _ symbol.

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0'] -> hold<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>>, '0'> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['1'] -> hold<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>>, '1'> -> (1, _, L),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, ' ', ^)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

We start expanding the parametrized TM that we delegate too. In the case of nested parametrized TMs we start with the outermost one.

:: hold ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1']+[' '] -> compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>> -> (ACC, '0', ^)

}

:: hold ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1']+[' '] -> compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>> -> (ACC, '1', ^)

}

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0'] -> (holdS0, _, ^),

holdS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>> -> (holdIntermediate0, '0', ^),

holdIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 ['1'] -> (holdS1, _, ^),

holdS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> compose<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '>, moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '>> -> (holdIntermediate1, '1', ^),

holdIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, ' ', ^)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

I have added the two hold definitions that were created to help in the visualization. Please refer back to the section on delegating transition if the expansion is not clear. We now expand the next outermost parametrized TM, compose.

:: compose ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1']+[' '] -> write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '> -> (1, _, ^),

1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (ACC, _, ^)

}

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0'] -> (holdS0, _, ^),

holdS0 ['0'] -> (composeS0, _, ^),

composeS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '> -> (compose01, _, ^),

compose01 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (composeIntermediate0, _, ^)

composeIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (holdIntermediate0, _, ^)

holdIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 ['1'] -> (holdS1, _, ^),

holdS1 ['1'] -> (composeS1, _, ^),

composeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> write<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' ', ' '> -> (compose11, _, ^),

compose11 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> moveRight<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (composeIntermediate1, _, ^)

composeIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (holdIntermediate1, _, ^)

holdIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, ' ', ^)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

We do this a few times until all the delegting transition are expanded:

:: write ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (ACC, ' ', ^)

}

:: moveRight ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (ACC, _, R)

}

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0'] -> (holdS0, _, ^),

holdS0 ['0'] -> (composeS0, _, ^),

composeS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeS0, _, ^),

writeS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeIntermediate0, ' ', ^),

writeIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (compose01, _, ^)

compose01 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (moveRightS0, _, ^)

moveRightS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (moveRightIntermediate0, _, R)

moveRightIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (composeIntermediate0, _, ^)

composeIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (holdIntermediate0, _, ^)

holdIntermediate0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 ['1'] -> (holdS1, _, ^),

holdS1 ['1'] -> (composeS1, _, ^),

composeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeS1, _, ^),

writeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeIntermediate1, ' ', ^),

writeIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (compose11, _, ^)

compose11 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (moveRightS1, _, ^)

moveRightS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (moveRightIntermediate1, _, R)

moveRightIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (composeIntermediate1, _, ^)

composeIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (holdIntermediate1, _, ^)

holdIntermediate1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (1, _, L),

1 [' '] -> (ACC, ' ', ^)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

We now expand the _ and ^ symbols to have our final TM:

:: rightShift ['0', '1'] ['0', '1']+[' '] {

S ['0', '1'] -> toEnd<['0', '1'], ['0', '1'], ' '> -> (1, _, L),

1 ['0'] -> (stay10, '0', R),

stay10 ['0'] -> (holdS0, '0', L)

stay10 ['1'] -> (holdS0, '1', L)

stay10 [' '] -> (holdS0, ' ', L)

holdS0 ['0'] -> (stayHoldS0, '0', R),

stayHoldS0 ['0'] -> (composeS0, '0', L)

stayHoldS0 ['1'] -> (composeS0, '1', L)

stayHoldS0 [' '] -> (composeS0, ' ', L)

composeS0 ['0'] -> (stayComposeS0, '0', R),

composeS0 ['1'] -> (stayComposeS0, '1', R),

composeS0 [' '] -> (stayComposeS0, ' ', R),

stayComposeS0 ['0'] -> (writeS0, '0', L)

stayComposeS0 ['1'] -> (writeS0, '1', L)

stayComposeS0 [' '] -> (writeS0, ' ', L)

writeS0 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (stayWriteS0, ' ', R),

stayWriteS0 ['0'] -> (writeIntermediate0, '0', L)

stayWriteS0 ['1'] -> (writeIntermediate0, '1', L)

stayWriteS0 [' '] -> (writeIntermediate0, ' ', L)

writeIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (stayWriteIntermediate0, '0', R)

writeIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (stayWriteIntermediate0, '1', R)

writeIntermediate0 [' '] -> (stayWriteIntermediate0, ' ', R)

stayWriteIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (compose01, '0', L)

stayWriteIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (compose01, '1', L)

stayWriteIntermediate0 [' '] -> (compose01, ' ', L)

compose01 ['0'] -> (stayCompose01, '0', R)

compose01 ['1'] -> (stayCompose01, '1', R)

compose01 [' '] -> (stayCompose01, ' ', R)

stayCompose01 ['0'] -> (moveRightS0, '0', L)

stayCompose01 ['1'] -> (moveRightS0, '1', L)

stayCompose01 [' '] -> (moveRightS0, ' ', L)

moveRightS0 ['0'] -> (moveRightIntermediate0, '0', R)

moveRightS0 ['1'] -> (moveRightIntermediate0, '1', R)

moveRightS0 [' '] -> (moveRightIntermediate0, ' ', R)

moveRightIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate0, '0', R)

moveRightIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate0, '1', R)

moveRightIntermediate0 [' '] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate0, ' ', R)

stayMoveRightIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (composeIntermediate0, '0', L)

stayMoveRightIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (composeIntermediate0, '1', L)

stayMoveRightIntermediate0 [' '] -> (composeIntermediate0, ' ', L)

composeIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (stayComposeIntermediate0, '0', R)

composeIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (stayComposeIntermediate0, '1', R)

composeIntermediate0 [' '] -> (stayComposeIntermediate0, ' ', R)

stayComposeIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (holdIntermediate0, '0', L)

stayComposeIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (holdIntermediate0, '1', L)

stayComposeIntermediate0 [' '] -> (holdIntermediate0, ' ', L)

holdIntermediate0 ['0'] -> (1, '0', L),

holdIntermediate0 ['1'] -> (1, '1', L),

holdIntermediate0 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L),

1 ['1'] -> (stay11, '1', L),

stay11 ['0'] -> (holdS1, '0', R)

stay11 ['1'] -> (holdS1, '1', R)

stay11 [' '] -> (holdS1, ' ', R)

holdS1 ['1'] -> (stayHoldS1, '1', R),

stayHoldS1 ['0'] -> (holdS1, '0', L)

stayHoldS1 ['1'] -> (holdS1, '1', L)

stayHoldS1 [' '] -> (holdS1, ' ', L)

composeS1 ['0'] -> (stayComposeS1, '0', R),

composeS1 ['1'] -> (stayComposeS1, '1', R),

composeS1 [' '] -> (stayComposeS1, ' ', R),

stayComposeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeS1, '0', L)

stayComposeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeS1, '1', L)

stayComposeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (writeS1, ' ', L)

writeS1 ['0', '1']+[' '] -> (stayWriteS1, ' ', R),

stayWriteS1 ['0'] -> (writeIntermediate1, '0', L)

stayWriteS1 ['1'] -> (writeIntermediate1, '1', L)

stayWriteS1 [' '] -> (writeIntermediate1, ' ', L)

writeIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (stayWriteIntermediate1, '0', R)

writeIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (stayWriteIntermediate1, '1', R)

writeIntermediate1 [' '] -> (stayWriteIntermediate1, ' ', R)

stayWriteIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (compose11, '0', L)

stayWriteIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (compose11, '1', L)

stayWriteIntermediate1 [' '] -> (compose11, ' ', L)

compose11 ['0'] -> (stayCompose11, '0', R)

compose11 ['1'] -> (stayCompose11, '1', R)

compose11 [' '] -> (stayCompose11, ' ', R)

stayCompose11 ['0'] -> (moveRightS1, '0', L)

stayCompose11 ['1'] -> (moveRightS1, '1', L)

stayCompose11 [' '] -> (moveRightS1, ' ', L)

moveRightS1 ['0'] -> (moveRightIntermediate1, '0', R)

moveRightS1 ['1'] -> (moveRightIntermediate1, '1', R)

moveRightS1 [' '] -> (moveRightIntermediate1, ' ', R)

moveRightIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate1, '0', R)

moveRightIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate1, '1', R)

moveRightIntermediate1 [' '] -> (stayMoveRightIntermediate1, ' ', R)

stayMoveRightIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (composeIntermediate1, '0', L)

stayMoveRightIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (composeIntermediate1, '1', L)

stayMoveRightIntermediate1 [' '] -> (composeIntermediate1, ' ', L)

composeIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (stayComposeIntermediate1, '0', R)

composeIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (stayComposeIntermediate1, '1', R)

composeIntermediate1 [' '] -> (stayComposeIntermediate1, ' ', R)

stayComposeIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (holdIntermediate1, '0', L)

stayComposeIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (holdIntermediate1, '1', L)

stayComposeIntermediate1 [' '] -> (holdIntermediate1, ' ', L)

holdIntermediate1 ['0'] -> (1, '0', L),

holdIntermediate1 ['1'] -> (1, '1', L),

holdIntermediate1 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L),

1 [' '] -> (stay1Blank, ' ', R)

stay1Blank ['0'] -> (ACC, '0', L)

stay1Blank ['1'] -> (ACC, '1', L)

stay1Blank [' '] -> (ACC, ' ', L)

2 [' '] -> (1, ' ', L)

}

And this is the final turing machine that we end up with. You can see it in action on turing-machine.io.

And if you’re wondering, like I would, if this expansion was done by hand, then yes it was! And I would not inflict this on my greatest enemy!

Some things could be split-up in smaller pieces, or compacted in bigger ones, but the granularity of the pieces depends on the context we are doing this in.

As an example piece, I found this level of granularity interesting enough to be observed.

My Tummy(s) is hurting!

While it was really funny to think about Tummys, I’m not completely satisfied by the current state of its design.

One glaring issue is that the expanded TMs that Tummys declares are much more tangled and riddled with unnecessary steps than the one we would write. With each level of indirection that we add, we add even more intermediary do-nothing steps.

Many of this are from “don’t move the head” expansions that are there because of the model we use for our transitions. But most of those “don’t move” transitions are derived from the expansions of all the delegations we do and their intermediary steps.

When I will get to work on Tummys I will surely check some of the expansion rules again. With many things removed from the core of the language, some of the intermediary steps we take feel unnecessary now.

Adding all those steps means making the TMs less performant too, as they do a larger number of steps than they need.

For example, the rightShift machine that we saw in the exercise can be easily written with about 5 states. Part of this can be easily solved in the compiler by doing some optimization passes that removes many do nothing steps. But, nonetheless, I still think that this can be solved at the root by remodelling some expansion rules.

The second thing I can’t feel happy about is the way in which the programming with Tummys feels. TMs are, by nature, imperative, mutating, state machine with side effects. I would have liked to be able, with Tummys, to abstract away the kind of imperative mentality that naturally comes by working on a turing machine configuration.

While I tried to provide abstractions that would lead towards some different mentality state, I don’t think this was successful enough.

While working through the examples you saw here, and other experimental programs, I did not feel like I was helped in thinking with the paradigm I was trying to express nor at the abstraction level I wanted.

At the same time, and in some way contrarily to what a research of such abstractions should bring, I feel there is a kind conflict between the tools Tummys provides and the way a TM can be easily reasoned about. Many times during the writing of these examples I felt that the complexities those abstractions create were completely unnecessary and as much as a, I dare say, disadvantage over the more concrete way TMs can be expressed.

I’m still not sure how those feelings should be addressed but I wouldn’t mind looking at Tummys from the inside out again when I will have more experience with this kind of things.

MOV MOV MOV MOV MOV MOV MOV MOV

Going back to the start, I said that Tummys was chosen because of this paper. For those that do not want to read it, the TLDR is that the x86 MOV instruction is Turing complete on its own ( and a single JMP instruction and four registers {or less for some programs}).

What this has to do with Tummys, is that Tummys was made because the real exercise I wanted to tackle was to build a bytecode VM which basically supports only a MOV-like instruction, and then build a compiler for some language that compiled to that VM bytecode. A language that worked with actual TMs seemed easier to translate than some other language with other constructs.

While this is what spawned this exercise, this is probably the thing that makes it the most inaccessible to me right now.

This is all speculative though, it may happen that it is actually an easy implementation to do and parsing Tummys becomes the actually hard part who knows.

“All shall be done, but it may be harder than you think.”

This is what I consider a cool exercise to try. Nonetheless, I’m not sure if I will tackle it right away. Unfortunately, my current study routine is completely packed by rotating between 2 programming books, 1 math book { which is slowing me down the most }, 2 MOOCs and a practical exercise where I bang my head against the wall while implementing a Bitmapped Vector Trie in C++. It is far more realistic that after completing the Crafting Interpreters book I will try my hand at something like the PL\0 at first.

So, why write all this?

Mostly because writing about this exercise was an exercise in itself ( and I needed to relax a little after some all-nighters and getting the damn Cold ). Basically, right now, a great focus of my studies is to build a better Math and CS foundation and Turing Machines were themselves something that I looked at again recently in more depth than the last time I studied them. It was really helpful brainstorming on this as an excuse to revise some TM concepts while, at the same time, looking at some of the learning I did on Crafting Interpreters from another angle. How I would parse this, Is this as expressive as it can, How would I define a Turing Machine that does X and such were all interesting question to explore this way.

At the same time, it helped me a little with trying to use a more rigorous and formal thinking and writing process. Anyone with real experience and knowledge is surely able to point me to thousands of things that I failed at in this regard, but this small steps are helping me a lot with slowly filling the gaps of a completely self-taught education that sometimes weights too much { My second greatest regret is probably that I was not able to follow a normal academic path }.

I hope this was at least a little bit interesting to someone else, I will probably try to write down a formal grammar for Tummys in my free-time-from-my-free-time for the time being while hoping to tackle this as soon as possible.