Case Study 1 Delta Mush - Part 3

by Luca Di Sera

The fun part begins

With the last post we reached a point were we finally had a real draft to start working on. In this post we are going to start looking at some more interesting optimization for our deformer. We’ll have a lot of pointers, some “clever” code and a LOT of less readable code ( if you’re not accustomed to it ) - exactly what I call fun coding. As I’ve done many modifications to the code - some reapeated troughtout it - for this post we will work somewhat in reverse. I will firstly show you the results of the optimizations and then we will talk about them with a specific example from the new code.

For reference, and please read it if you find something interesting in this post ( critics, comments, and suggestion are much much appreciated ), here is the diff between the last and the current version of the code which is pretty much unrecognizable.

Some Numbers

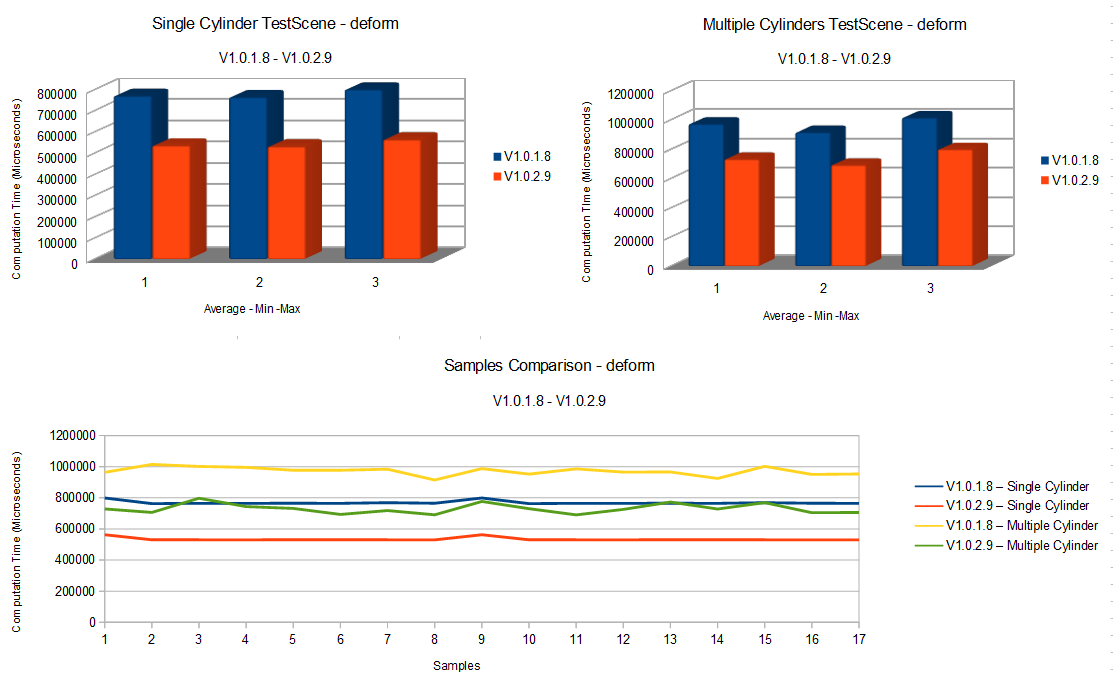

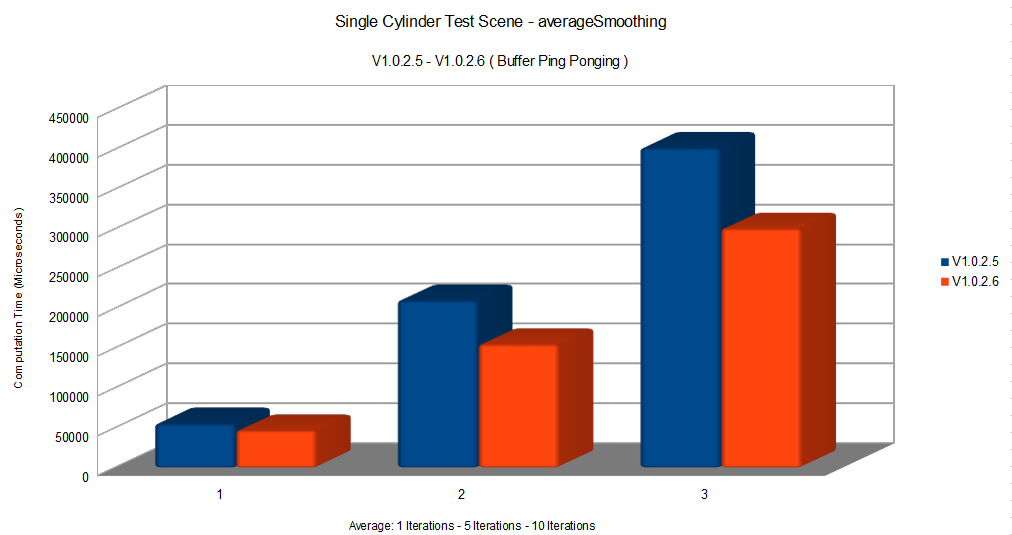

So, the first interesting bits: The code is about 43% faster on the one cylinder scene and 33% faster on the multiple cylinder scene. Here are some graphs:

As you can see the performance improved a lot. Let’s see how this was done.

A preambole to this discussion

Something important that I’d like to talk about is timing your code. This is really important to do. All of the optimizations done in this post were completely timed at different granularities multiple times. Some optimizations that I tried were actually detrimental to the code and I had to revert them. Apart for some things that are obvious ( like the last post optimizations ) never take something you do for granted. Timings are the only truths about optimizations and everything should be checked.

Another thing that is important, is the sequences of the optimizations. As this is a didactical study I’m jumping liberally between the code and optimizing where I feel like it. In a production environment, where time is money, optimizations are a costly thing. They take time, trial and error, and (usually) reduce the maintanability of the code by making it less readable, expressive and/or more difficult. This means that optimizations should be done firstly, and sometimes only, where timings demonstrate that there is a real bottleneck.

Now we can jump to the code.

Optimizations

Bypassing Maya Containers Overhead

Maya containers are oh so slow. This was something that was told to me. I must say that, for how much I accepted it as truth, I could not really understand how much slow they are until I had seen it with my eyes. For this reason I will start this part by showing you two examples of the result of removing some of maya containers usage in this deformer.

If this is not convincing you, or even if it is actually, you should try it yourself. But how do we bypass them you may ask? This is actually a good question. We cannot eliminate them completely as they are expected by some of the Maya API methods that we must use. What we can usually do is not using their methods and operators by accessing their memory manually. One interesting thing is that, for example, an MPoint has its x, y, z and w members in a contiguos memory space. What this means, is that by accessing the memory location of the first member ( x ) we can traverse them all by jumping double-length chunk of memory.

For example:

MPoint point{};

double* pointPtr{ &point.x };

pointPtr[0]; // point.x

pointPtr[1]; // point.y

pointPtr[2]; // point.z

pointPtr[3]; // point.w

Even more interesting is the fact that maya containers like MPointArray and MVectorArray present the same contiguos memory for their members. This means we can do something like the following:

MPointArray points{4};

double *pointPtr{ &points[0].x };

for ( int vertexIndex{ 0 }; vertexIndex < 4; ++vertexIndex, pointsPtr += 4 ) {

pointPtr[0] += 1.0;

pointPtr[1] += 1.0;

pointPtr[2] += 1.0;

pointPtr[3] += 1.0;

And traverse the whole array double by double. As you’ve seen at the start of this section this gives us the possibility of having a great speed improvement. Let’s see an example of it.

MVector DeltaMush::neighboursAveragePosition(const MPointArray & verticesPositions, unsigned int vertexIndex) const

{

unsigned int neighbourCount{ neighbours[vertexIndex].length() };

MVector averagePosition{};

for (unsigned int neighbourIndex{ 0 }; neighbourIndex < neighbourCount; neighbourIndex++) {

averagePosition += verticesPositions[neighbours[vertexIndex][neighbourIndex]];

}

averagePosition /= neighbourCount;

return averagePosition;

}

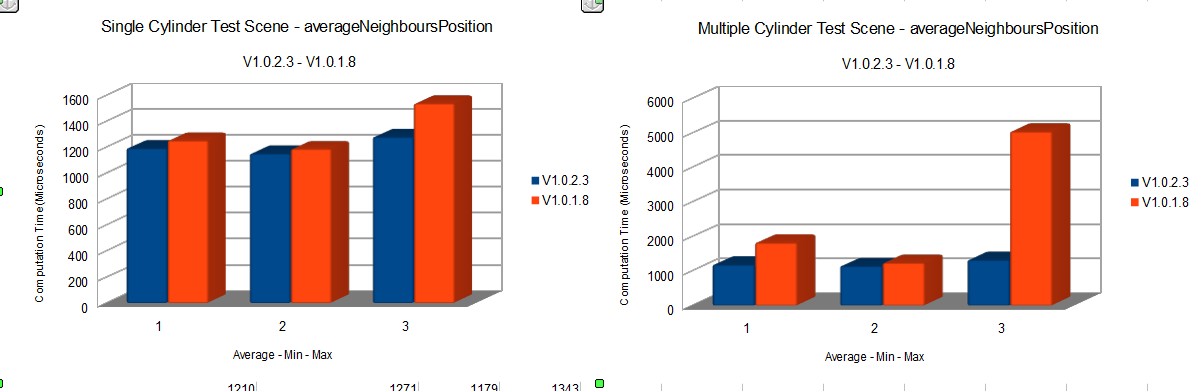

We had this code in our deformer. The speed improvement we will get from the following exercise is the one in the first image of this section. First we have to look at what containers we are using and how. We have an MPointArray in verticesPositions, an MVector in averagePosition, and a std::vector<MIntArray> in neighbours. neighbours is traversed sequentially by ints so we can move the pointers along with the loop. verticesPositions is, instead, traversed in a non-sequential order. This means that we need it to reference the first element and dereference accordingly ( or indexing accordingly as we are in c++ ) or to move it every loop iteration by getting the memory address of the first element and adding to it. I chose the latter for this code. First let’s access the containers with pointers.

MVector averagePosition{};

const double* vertexPtr{ &verticesPositions[0].x };

double* averagePtr{ &averagePosition.x };

const int* neighbourPtr{ &neighbours[vertexIndex][0] };

vertexPtr does not necessarily need initialization for how we are using it so bear that in mind. So we know that neighbours is accessed sequentially one int at the time. Then we can just increment it in the loop without the need for complex and dynamic indexing.

for (unsigned int neighbourIndex{ 0 }; neighbourIndex < neighbourCount; neighbourIndex++, neighbourPtr++)

A note here. pre-increment is faster that post-increment as one less temporary variable needs to be created. This is only a small change and your compiler should be, usually, able to optimize it for you but it is good practice to use pre-increment when post-increment is not needed. With this we can access the current int as easily as:

neighbourPtr[0]

// or

*neighbourPtr // you should just use the index operator in c++ tough

We could as easily have done it by keeping the pointer at the first member and indexing it accordingly as follows:

neighbourPtr[neighbourIndex]

But I think incrementing the pointer is a more expressive way to indicate the sequential access we are doing. I don’t know if there is a performance difference between the two. With cachelines, memory accesses, compilers interpretation etc… everything can be but it isn’t something to care about right now.

Getting back in-topic, we can start transforming the code to use this pointers we made. Sometimes this is a complex matter, especially if it is the first time you’re doing this ( but really, even if you’re an expert ) it is a good idea to change a few lines at the time and then test if everything is working correctly. At least this is my workflow ( with different step-sizes depending on what piece of code I have in front ). Anyway, let’s see an example of it with the only operation on our loop:

// averagePosition += verticesPositions[neighbours[vertexIndex][neighbourIndex]];

vertexPtr = &verticesPositions[0].x + (neighbourPtr[0] * 4);

averagePtr[0] += vertexPtr[0];

averagePtr[1] += vertexPtr[1];

averagePtr[2] += vertexPtr[2];

First thing first, as we said, verticesPositions is accessed non-sequentially, as such we have to jump around to the correct position every iteration. To do this we find the index of the neighbour vertex we need to access:

neighbourPtr[0]

Remember this is indexed at zero because we are incrementing it every iteration. We multiply it by 4 because the index refers to the MPoint in the MPointArray. We are thinking in doubles here and every MPoint has 4 doubles worth of memory to jump. So to jump to index 64 we need to jump 64 * 4 doubles, for example. And then add it to the starting member of the first MPoint in the array.

&verticesPositions[0].x + (neighbourPtr[0] * 4);

By assigning this memory address to vertexPtr we find us perfectly aligned to the first member of verticesPositions[neighbours[vertexIndex][neighbourIndex]] .

Now we only need to add this MPoint to the average variable.

averagePtr[0] += vertexPtr[0];

averagePtr[1] += vertexPtr[1];

averagePtr[2] += vertexPtr[2];

As we are working with doubles and not MPoint we have to do it manually. This will be true of a lot of operations we are going to do. This should be more that understandable by now. Both pointers are aligned to the first member ( x ) of their respective container. By jumping 0 doubles we access x, with 1 we access y and with 2 we access z. Nothing more simple. This is it. We actually removed the use of most of maya containers in the method. There are a lot of examples of this in the code so, if you’re interested, you can look there. Another really important advantage of this technique is that by reducing everything to sequential doubles memory pointers we are setting ourselves in a great position to vectorise our code with intrinsics. This will be a huge improvement in performance.

Other changes to neighboursAveragePosition

As this was the first method that I worked on for this version I’ll keep talking about it. There were some other things I did to it. We’ll skim them more rapidly. Plese refer to the code or ask me if you have questions.

First a really small optimization:

averageFactor = (1.0 / neighbourCount);

averagePtr[0] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[1] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[2] *= averageFactor;

Instead of dividing the vector we can multiply by the inverse of the division to have the same effect. This lets us cut 3 divisions to 1 which is a good thing. Then I tried giving an hint to the compiler by inlining the function. This method got called once per every vertex and the overhead This was something that I had to test too. Inling isn’t always a good thing and sometimes can make the performarmance worse. This was the case. So I reverted it.

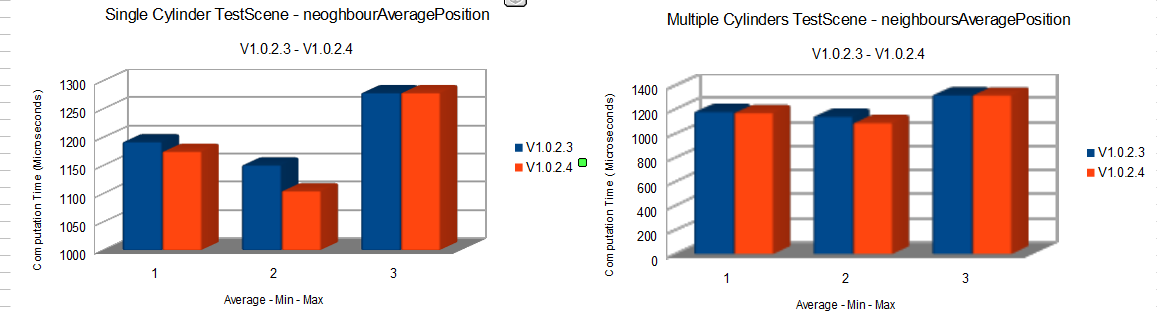

I then changed approach and deleted the method, moving it directly inside averageSmoothing. This has multiple advantages, like removing the function call overhead and making it possible to move the declaration of the needed variables outside the loop.

for (unsigned int vertexIndex{ 0 }; vertexIndex < vertexCount; ++vertexIndex) {

neighbourCount = neighbours[vertexIndex].length();

//resetting the vector

averagePtr[0] = 0.0;

averagePtr[1] = 0.0;

averagePtr[2] = 0.0;

neighbourPtr = &neighbours[vertexIndex][0];

for (unsigned int neighbourIndex{ 0 }; neighbourIndex < neighbourCount; ++neighbourIndex, ++neighbourPtr) {

vertexPtr = verticesPositionsCopyPtr + (neighbourPtr[0] * 4);

averagePtr[0] += vertexPtr[0];

averagePtr[1] += vertexPtr[1];

averagePtr[2] += vertexPtr[2];

}

// Divides the accumulated vector to average it

averageFactor = (1.0 / neighbourCount);

averagePtr[0] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[1] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[2] *= averageFactor;

// Store the final weighted position

currentVertex = vertexIndex * 4;

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex] = ((averagePtr[0] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 1] = ((averagePtr[1] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 1]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 1];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 2] = ((averagePtr[2] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 2]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 2];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 3] = 1.0;

}

This has led to interesting results which you can see in the graph:

This was mostly what I did. Let’s move on.

Buffer Ping ponging

I then moved to work on averageSmoothing. Apart from the many optimizations we had already seen there was something that was bugging me:

verticesPositionsCopy.copy(out_smoothedPositions);

We were copying all this data for every iteration. This was needed as we had to work on the updated data while keeping a place where we could store the newly calculated data. There is a way we can actually remove this copy with a much more efficient operation.

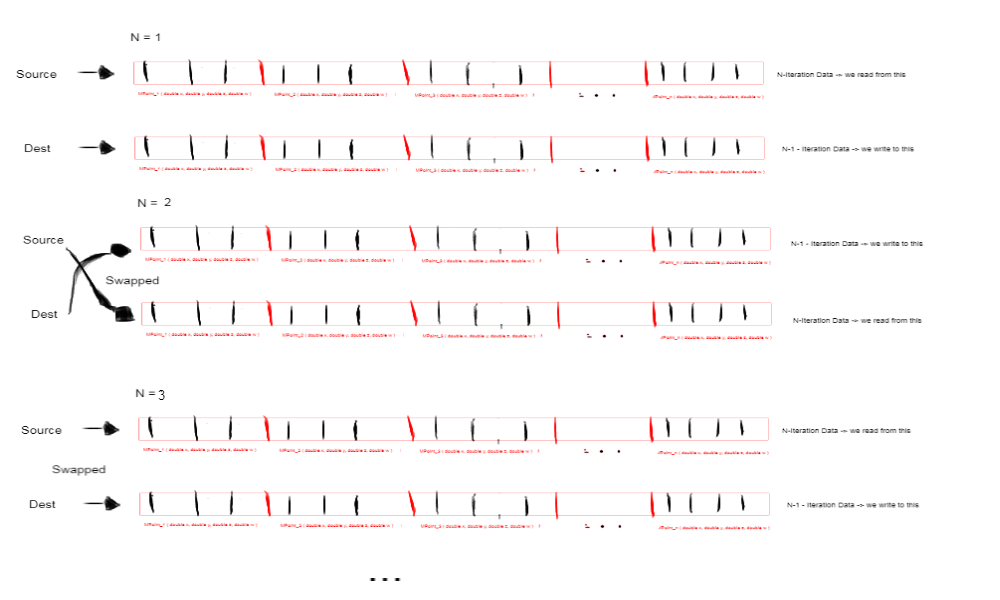

Bear with me. For all our intents and purposes verticesPositionsCopy and smoothedPositions presents an equivalent memory disposition. They are both they same size, they are both contiguos doubles in memory and they present the same meaning in their addresses ( the first double is vertex 0 x member for both ). The only difference is that one contains the positions updated to the last iterations and one doens’t. This is why we copy it, because we need the updated positions to read and we need a space in memory to write to ( and since the access is non sequential we can’t override the some of the vertexes data since we could need to access them again ). But as we said, from our point of view they’re mostly equivalent. Why don’t we just swap them then? After moving to a pointer based method we will find ourselves with a pointer that points to the array we read our data from, let’s call it source, and a pointer which points to where we store the newly calculated data, let’s call it dest. Instead of copying the data from one to the other we could just swap them, so that source reads from the already updated data we wrote on and dest writes to the array with the now useless old data. This let’s us have work with the correct data while having a memory space to write to without copying or overwriting the data we need.

I drew an image that should help visualize what we are doing here:

Now when we have our pointer in place:

//Declaring the data needed by the loop

MVector averagePosition{};

unsigned int neighbourCount{};

double* averagePtr{ &averagePosition.x };

const double* vertexPtr{};

const int* neighbourPtr{};

double averageFactor{};

int currentVertex{};

double* outSmoothedPositionsPtr{ &out_smoothedPositions[0].x };

double* verticesPositionsCopyPtr{ &verticesPositionsCopy[0].x };

for (unsigned int iterationIndex{ 0 }; iterationIndex < iterations; ++iterationIndex) {

// Inrementing the pointer by four makes us jumps four double ( x, y, z , w ) positioning us on the next MPoint members

for (unsigned int vertexIndex{ 0 }; vertexIndex < vertexCount; ++vertexIndex) {

neighbourCount = neighbours[vertexIndex].length();

//resetting the vector

averagePtr[0] = 0.0;

averagePtr[1] = 0.0;

averagePtr[2] = 0.0;

neighbourPtr = &neighbours[vertexIndex][0];

for (unsigned int neighbourIndex{ 0 }; neighbourIndex < neighbourCount; ++neighbourIndex, ++neighbourPtr) {

vertexPtr = verticesPositionsCopyPtr + (neighbourPtr[0] * 4);

averagePtr[0] += vertexPtr[0];

averagePtr[1] += vertexPtr[1];

averagePtr[2] += vertexPtr[2];

}

// Divides the accumulated vector to average it

averageFactor = (1.0 / neighbourCount);

averagePtr[0] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[1] *= averageFactor;

averagePtr[2] *= averageFactor;

// Store the final weighted position

currentVertex = vertexIndex * 4;

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex] = ((averagePtr[0] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 1] = ((averagePtr[1] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 1]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 1];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 2] = ((averagePtr[2] - verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 2]) * weight) + verticesPositionsCopyPtr[currentVertex + 2];

outSmoothedPositionsPtr[currentVertex + 3] = 1.0;

}

This became as simple as this:

std::swap(outSmoothedPositionsPtr, verticesPositionsCopyPtr);

The only thing we need to be caerful about is the final position of our updated data. As we have a variable number of iterations, and as such of swapping, but we always need our final data to be on out_smoothedPositions - we have to add a little bit of code before returning:

if ((iterations % 2) == 0) {

out_smoothedPositions.copy(verticesPositionsCopy);

}

Now I don’t like this. I’d like to find a way to avoid this code if possible but for now this has to do. I’m pretty sure we could just move instead of copy here but MPointArray does not seem to provide move assignment.

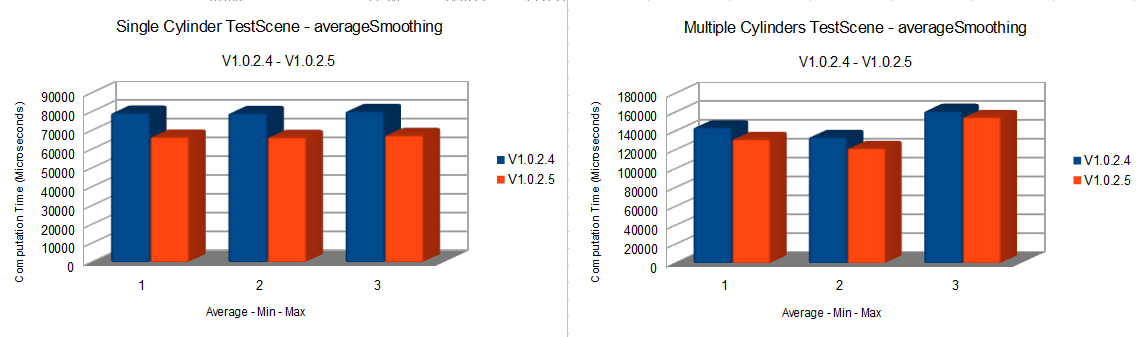

For how simple it was this gave us the possibility of removing a really expensive operation. You don’t have to trust me, just look at the following results and try it yourself:

Aligning our vector directly on a matrix

In the code we have this method to build our tangent space matrix:

MStatus DeltaMush::buildTangentSpaceMatrix(MMatrix & out_TangetSpaceMatrix, const MVector & tangent, const MVector & normal, const MVector & binormal) const

{

// M = [tangent, normal, bitangent, translation(smoothedPosition]]

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[0][0] = tangent.x;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[0][1] = tangent.y;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[0][2] = tangent.z;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[0][3] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[1][0] = normal.x;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[1][1] = normal.y;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[1][2] = normal.z;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[1][3] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[2][0] = binormal.x;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[2][1] = binormal.y;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[2][2] = binormal.z;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[2][3] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[3][0] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[3][1] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[3][2] = 0.0;

out_TangetSpaceMatrix[3][3] = 1.0;

return MStatus::kSuccess;

}

Well, this is just ugly. We’re going to look at a way to make this code more elegant and performant. First I deleted the method and moved the code in the right place ( as we still have some code duplication between cacheDeltas and the delta application there were two places to move it to ).

Then, before looking at the code, let’s do a bit of brainstorming. What we are doing here is preparing some MVectors and the copying their value into the matrix. But what are, more instrinsically, the vectors we are using and our matrix?

Internally, an MMatrix is just a double[4][4] memory space ( not exactly with it being a class and all but the memory that interests us is just that ). MVectors, instead, are containers for double[3]. What we are doing is making operations on those double[3] and then inserting them into the double[4][4] matrix. Maya’s matrix are padded, this means that the last column is, usually, uninteresting to us. So we can simplify what we need to a double[4][3] memory space.

By now you should be seeing it : We already have our essential vectors allocated by the matrix All of the vectors operation we are doing works on those double[3] memory spaces. If we can get our vectors double[3] to reside in the matrix space we can avoid copying the data by working directly inside the matrix. This is easily done, we don’t need to allocate or use the MVectors at all, we can just use our matrix space.

MMatrix tangentSpaceMatrix{};

double* tangentPtr{ &tangentSpaceMatrix.matrix[0][0] };

double* normalPtr{ &tangentSpaceMatrix.matrix[1][0] };

double* binormalPtr{ &tangentSpaceMatrix.matrix[2][0] };

The matrix member of MMatrix we are accessing is just that double[4][4] space we were talking about. An important thing to note is that the MMatrix default constructor allocates the space as the 4x4 identity matrix. This means that we find ourselves with the last row ( as we need our translate to be zeroed ) and the last column with the already correct values we need. Knowing that we just need to work on a simplified double[3][3] space, noneother than our 3 vectors.

Now there are 2 ways to approach this that I know. The first depends on an interesting trivia we can see. MVectors seem to reside in memory with their x, y, z members as the first memory block in its space ( 3 doubles worth of memory ). Furthermore all of the operations we do on them should write and read only that memory. As such, we find our double[3] aligned with an MVector even if it isn’t.

This means we can let the code think we are working with actual MVectors and use the class method on our matrix’s vectors:

// TODO : remove the unsafe casting and provide a custom normalization

((MVector*)(tangentPtr))->normalize();

((MVector*)(normalPtr))->normalize();

Now, this works, for now, but I don’t consider this safe or good at all. We don’t know how the object is actually layed out in memory nor how it works internally. A better method is to provide our calculation for the operations we have to do:

// Ensures axis orthogonality through cross product.

// Cross product is calculated in the following code as:

// crossVector = [(y1 * z2 - z1 * y2), (z1 * x2 - x1 * z2), (x1 * y2 - y1 * x2)]

binormalPtr[0] = tangentPtr[1] * normalPtr[2] - tangentPtr[2] * normalPtr[1];

binormalPtr[1] = tangentPtr[2] * normalPtr[0] - tangentPtr[0] * normalPtr[2];

binormalPtr[2] = tangentPtr[0] * normalPtr[1] - tangentPtr[1] * normalPtr[0];

normalPtr[0] = tangentPtr[1] * binormalPtr[2] - tangentPtr[2] * binormalPtr[1];

normalPtr[1] = tangentPtr[2] * binormalPtr[0] - tangentPtr[0] * binormalPtr[2];

normalPtr[2] = tangentPtr[0] * binormalPtr[1] - tangentPtr[1] * binormalPtr[0];

This is fast, easy and safer than casting to MVectors. Most of the vector’s operations are just applying a formula to the 3 members and nothing else. If you want to simulate the MVectors you could even get the code from MVector.h and use it for the operations:

/*!

Performs an in place normalization of the vector

\return

Always returns MS::kSuccess.

*/

inline MStatus MVector::normalize()

{

double lensq = x*x + y*y + z*z;

if(lensq>1e-20) {

double factor = 1.0 / sqrt(lensq);

x *= factor;

y *= factor;

z *= factor;

}

return MStatus::kSuccess;

}

This is the code for normalize for example. But this is just unnecessary considering the simplicity of the operation.

Now, here we could actually remove the matrix completely and just work with a double[4][4] ( the other interesting thing about all of this is that, where we don’t need the precision, we can the transform all this data to floats and vectorise it to move less memory per value and look if it improves performance ). I haven’t tried&timed it yet but I think it should be a good idea. Will probably do sooner or later.

Now, after all this work do we have anything to brag about? Absolutely yes. Unfortunately I don’t have a graph to show to you this time. I was sure to have saved the data for it but it seems I have not. So forgive me, but this is a great oppurtunity to try it yourself if you’re interested.

Conclusions

This is what I wanted to show you in this post. There are other changes that I made, as said refer to the code for them. If you’re like me, we are finally at the fun part of this case study. I suggest that you try working on the previous version of the code ( or better yet a version of your own ) and try all of those things yourself. They’re beatiful to look at but the real fun lies in looking at the code and thinking about the what, how and where.

There are many other things I’d like to try, especially things I’m recently studying like loop unrolling, loop blocking or making the number of neighbour iterations fixed ( approximating the result ). There are things to clean, I think I have left some containers usages and some dirty code here and there. I will work and try them eventually. Some of those things will just go away with us restructuring the code.

I may do another post on them next time but we are probably just jumping on the intrinsics train with AVX and vectorising our code next time.

See you next time!